Manchester - Brief History and Architecture

- Madeline Wynne

- Jun 30, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Jul 11, 2021

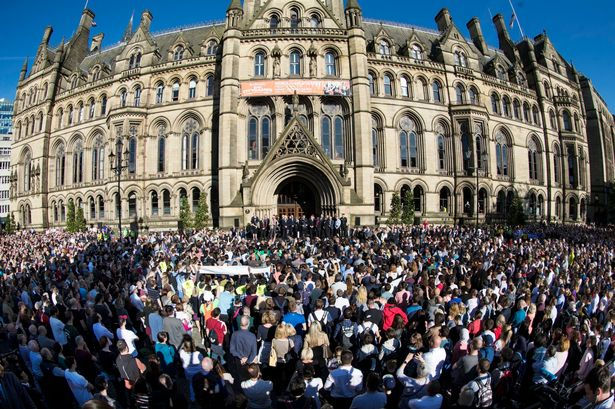

I have come to the conclusion that the architecture alone is not unique, and I cannot look at the architecture alone, without considering the personal and collective history of my home city. For example, I love the town hall in Manchester, for three reasons. Firstly, I stood opposite it for years waiting for my bus to school, and my daily journey has made me familiar with its ironwork, stone carvings, etched windows and architectural details. Secondly, different generations of my family made similar journeys through the city and past the same buildings, so as I walk around the city I am reminded of family stories of aunts and uncles and grandparents, and feel as if I am walking in their footsteps. Thirdly, I am aware that the town hall in Manchester is steeped in local history. It was built with money from the textile trade as a time of great civic pride, its distinctly Mancunian features include bees and cotton motifs, and the Ford Madox Brown 'Manchester murals' showing the history of the city and its people. It is still at the centre of cultural life, being the place where the poet Tony Walsh read his poem during the vigil after the terrorist bomb, where Father Christmas scales the clock tower every year during the Christmas Markets, and where blue footballing successes are celebrated.

I think that I need to add some historical context to my Mancunian architecture. I need to broaden my research to look at the time when Manchester was at the peak of its wealth and influence. When the history and architecture of Manchester came together to produce something that will distinguish it from other cities. This seems to me to be when the city was at the forefront of both the industrial revolution, and architectural change. Maybe a deeper investigation of history and architecture, will reveal the essence of the city, and what it was like to be there at different times in history. This might lead me towards what this city is about, and from there what it means to me, and to my family.

Manchester Cathedral

Manchester was a relatively small place based around the current cathedral site for many years. It lacked strong local government and craft guilds: this would ultimately prove beneficial, as early growth of the business community was unrestricted. By the 16th century it had a healthy hand-weaving tradition, using wool, linen and eventually cotton in its fustian, and had established a national reputation for good quality textiles, even before the first factory was built. It gradually became a regional focus for buying and selling textiles, Sir Oswald Mosley opened the first exchange building in 1729. With increased wealth, access to canal and river transport, local supplies of coal, steam powered expertise, and a growing population it was well placed to expand rapidly during the industrial revolution. Unlike other regional towns, Manchester did not rely solely on cotton manufacture. The expansion of the cotton trade drove developments in the related engineering and chemical industries. These industries would become significant contributors to the local economy.

Trading at the Royal Exchange

Driven by the textiles trade, wealth flooded into the city, and accumulated in the hands of merchants and financiers. The prominent industrialists of Manchester created a huge demand for property, commercial buildings, steam-powered mills, warehouses, exchanges and trading offices, as well as public buildings and amenities. They established libraries, institutes and apprenticeships to promote and widen education and learning. They were interested in engineering and science, and set up societies to study these subjects. Owens college set up the first university department focused on organic chemistry, manned and led by a combination of scientists and industrialists.

Architecture in the early nineteenth century was predominately focused on two trends, Classical and Gothic Revival. The Classical style was heavily influenced by archaeological discoveries. Books described Greek and roman buildings in detail and incorporated illustrations that were readily adopted as the standard of good taste. The second trend, Gothic-Revival looked back to the middle ages, it initially appeared in churches, but then in public buildings, a style epitomised by Pugin. All of this was about to change, and Manchester led that change.

In the mid 19th century three factors caused architects to look for alternatives to the prevailing style. Firstly, new building materials were becoming available, in particular cast iron, used initially by engineers who were able to identify its potential for buildings. Cast iron columns gave the possibility of building taller and larger buildings, as well as providing a degree of protection against fire. Secondly, the expansion of manufacturing was also having an effect, smoke and pollution was an increasing problem, blackening the stone built buildings of the cities. The architect William Butterfield provided a possible alternative to stone that was less affected by pollution. In All Saints church in London, he used polychrome brickwork to provide bands of colour and elaborate decoration on the outside and ceramic tiles on the inside. (Polychromy is the use of colour in architectural details, such as brickwork, ceramic tiles or sculpture). Thirdly, at around the same time, in 1849, John Ruskin wrote The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and The Stones of Venice praising Northern Italian Medieval Gothic and Northern Italian Rennaisance buildings, and in particular the use of decorative external surfaces and features.

Victorian architects, and society, embraced these new materials and ideas, and abandoned the notion of design purity and rigidity. The architects started to work more creatively, picking and choosing elements from a range of design styles to meet the particular needs and circumstances of their clients. Initially the canal warehouses were functional rather than decorative, they were closer to river, canal and railway access, such as in the Castlefield and Ancoats areas. However new demand developed for selling or carriers warehouses to display as well as store textiles. Mancunian clients were receptive to Ruskin's Italian rennaisance style of architecture, as the large multi - storey buildings suited their needs for showrooms and stockholding. The city states of Venice and Florence were built by people like themselves, traders, scientist and innovators, and this also added a certain desirability. Over the next 20-40 years as trade boomed the warehouses became more lavish to attract customers and denote high levels of quality and customer service. Colourful brick palazzo style buildings sprang up in Manchester from the 1830's, and became the predominant style of the industrial revolution. The architects selected freely from all these influences, producing a mixed bag broadly recognised as 'Victorian' architecture.

The three buildings below were built in this period. Charlotte Street, on the left, was one of the first such buildings, finished in 1839. The peak of this Victorian building style can be seen in Manchester town hall in the centre, which has elements of many styles from gothic to renaissance. It was completed in 1887, by mancunian Alfred Waterhouse. On the right, is Watts Warehouse, it was the largest single-occupancy warehouse in Manchester, and each floor was decorated in a different architectural style. It was built by the local firm of architects Travis & Mangnall.

Whilst there was great wealth, architecture and opportunity in the city for some, there was also poverty, poor sanitation and appalling living conditions for many. Friedrich Engels wrote that 'the working people's quarters are sharply separated from the sections of the city reserved for the middle-class. In his book 'The Condition of the Working Class in England', written in German in 1845, he described the shocking living conditions of workers in areas like Angel Meadow and Ancoats.

I feel as if I have a better understanding of why the city looks like it does, and why it is dominated by palazzo style warehouses. My familiarity with the city and its main thoroughfares meant that I knew most of the buildings were of a similar height and design, and do indeed look like renaissance palaces. This knowledge was not really explicit or conscious, and was certainly was not connected to the architecture and urban history of Manchester.

I can see the city more clearly now, but I also have an idea of when individual buildings were built, and can make personal links between the city and my own family history. I have an idea of what the city looked like when my grandparents arrived in Manchester. I know what there are buildings and streets, that are unchanged today, that they could have walked past. Buildings they may have visited, train stations, hospitals, churches, parks, the art gallery. I know that the dates of some buildings coincide with dates in my family history, Manchester Central Library did not exist when my grandparents arrived in Manchester, and was built at about the same time as my mum was born. The dates of the building of the library mean that it was always part of my mums experience of the city, whereas it was a change for my grandparents, who would probably have watched it being built and read about its opening in the local press.

My experience of the city is of course very different, but within all the change and regeneration, some elements remain the same. Old photographs suggest that Watts Warehouse, and the Town Hall are virtually unchanged. My grandfather, and my mother and I would be able to recognise them. Some areas of the city have witnessed little change whereas others have frequently been developed and regenerated. I am interested in the idea that current generations walk a path that has been walked by previous generations, and whilst the path may be exactly the same, the surroundings are different. Maybe there are some buildings that remain the same to both viewers, but other buildings appear for a generation and are then replaced, layer upon layer..

Comments